Styles and Categories

Which categories should be used to describe modern Balinese sculpture? The question is a difficult one. The categories I propose here are based as much on what I have learned from exchanges and readings as on my own observations. They therefore contain an element of subjectivity and do not claim to provide an exhaustive or definitive answer to the question.

Traditional Style

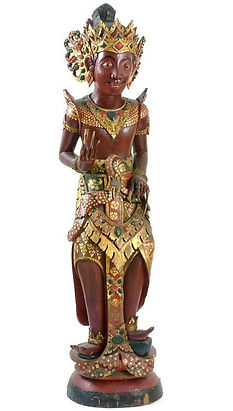

The term “traditional style” can be used to describe a mode of representation frequently employed at the beginning of the 20th century, and sometimes later, in the depiction of deities, characters, or episodes drawn from the great narratives of Hinduism. Statues produced in this style resemble certain characteristic pieces from the late 19th century, fine examples of which can be found in the collections of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (Netherlands), although they are generally smaller in scale.

Moderately realistic forms and codified gestures remain faithful to types inherited from tradition. This style tends to favor a frontal posture, often symmetrical and static, particularly in the depiction of single figures. When the statue is not polychrome, the wood used is often dark, with a reddish-brown hue. The finest works in this style are distinguished by an abundance of finely carved detail, both in garments and in adornments.

Left: Waruna, before 1900, 116.5 cm, polychrome wood, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, under Creative Commons license

Right: Rama, first half of the 20th century, 31.5 cm, private collection

The statue representing Waruna is part of a series of twenty-eight figures of Balinese deities commissioned by the National Ethnographic Museum of Leiden to be displayed in the Dutch colonial section of the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle. Like many traditional statues, it is polychrome and large in size. Carved in natural wood and on a smaller scale, the statue of Rama illustrates the adaptation of the traditional style to the tourist market.

Modernized Traditional Figures

The notion of style is of limited use in describing this rather heterogeneous group, which I suggest includes representations of traditional figures and episodes when they depart, to varying degrees, from classical conventions. This trend became particularly pronounced after independence, with the development of galleries. The interpretation of motifs may involve a stronger pursuit of naturalism or a diversification of postures. It may also manifest through a departure from classical iconography, especially in the depiction of attributes—whether as a result of creative license or of a more limited familiarity with iconographic canons on the part of some sculptors. In certain cases, these liberties taken with traditional iconography can make it more difficult to identify the figures or subjects represented.

Realism

Some sculptures reveal a particular concern for fidelity to observed reality, especially in their anatomical accuracy and in the treatment of forms, expressions, and postures. This realistic tendency was already very present in the first half of the 20th century, notably in the making of busts. More broadly, it can also be seen in representations of scenes from everyday life and, to a lesser extent, in certain depictions of animals.

A modernized traditional figure: Dewi Sri by I Wayan Narta, second half of the 20th century, 49 cm, private collection

An example of realistic sculpture: Bust of a young man by I Made Pait, 1930s–1940s, 36.5 cm, private collection

Wayang Style

This style was practiced mainly in the 1930s and 1940s. Its formal resemblance to certain creations of the Art Deco movement, which was fashionable in Europe and the United States in the 1920s–1930s, led some to assume that it originated from Western influence, hence the label “Art Deco style”—a term still frequently used among collectors. While Western influence cannot be entirely ruled out (Bali having been a crossroads of cultures since the early 20th century), Koos van Brakel has shown that the characteristics of this style derive more naturally from a transposition, into wood sculpture, of features already present in traditional shadow puppets, or wayang kulit. The term “Wayang style” thus seems more appropriate.

Elongation dominates the proportions, which are generally unnatural. The silhouettes are slender. The arms—like those of the puppets—are formed of narrow, elongated cylinders, while the legs often remain fuller. The face typically shows pronounced eyebrows arching over almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, a thin and long nose, and prominent lips. The ears are often large and set rather high. Fingers are exaggeratedly long and narrow, often showing a double incision at the base of the nail. From one sculpture to another, the manner and degree of simplification or geometrization of forms may vary considerably. The most refined works produced in this style are now among the most sought-after pieces by collectors.

Wayang puppet representing Rama, before 1966, approximately 45 × 15 cm, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, under Creative Commons license

Woman in prayer in the wayang style, 1930s or 1940s, 30 cm, private collection

Elongated Style

This so-called “elongated” style appeared in the mid-20th century, through the exploration of possibilities offered by the free interpretation of proportions and the elongation of figures already practiced in the Wayang style—hence it has also been described as a variant of the “Art Deco” style. It became the favored ground of sculptors such as I Wayan Wiri and I Made Runda. At times, it leads to a kind of mannerism based on undulating or contorted effects of varying extravagance.

Rounded Forms style

Another important style, to my knowledge lacking a conventional English name. I propose “Rounded Forms Style.” Created in 1956 by Ida Bagus Njana with his famous sculpture of a sleeping woman (now in the Puri Lukisan Museum), this style—marked by soft, rounded forms—is often used for humorous and tender representations of sleepers, couples, pregnant women, or mothers with children. It lends itself particularly well to a play between carved volumes and the highlighting of natural wood patterns. It is one of the preferred styles of prominent sculptors such as Ida Bagus Tilem and I Wayan Purne.

An example of the rounded forms style: Woman and children by I Wayan Gejir, second half of the 20th century, 25.5 cm, private collection

A figure in the elongated style, 1950s, 42 cm, private collection